1. Japanese corporate earnings have bottomed as a result of reforms

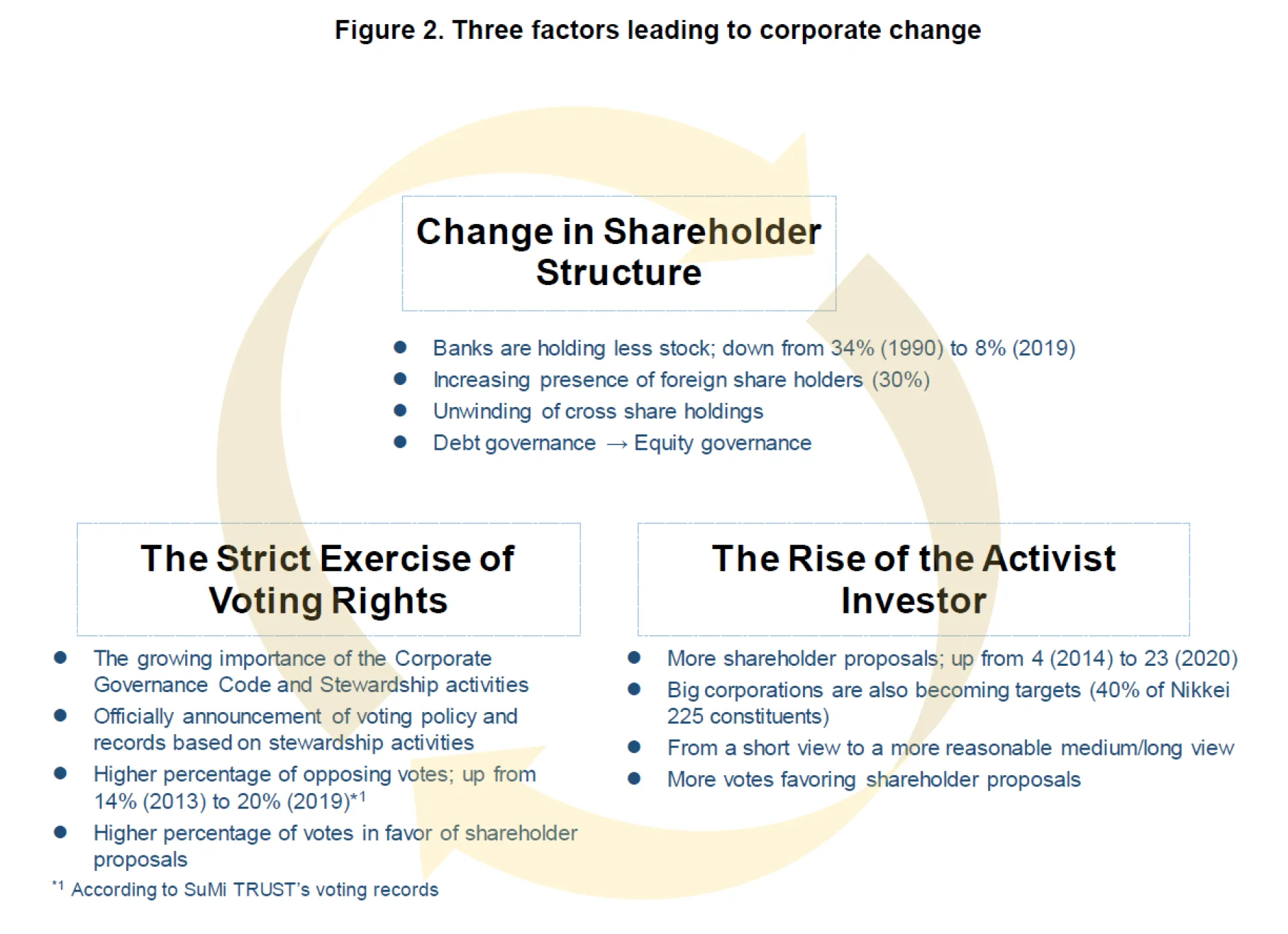

We seem to have found a bottom in corporate performance. Summarizing the performance of companies (listed on the First Section of the TSE) whose quarter ends in March, June, September and December, operating income at the end of September was down 25% YoY. We see a clear evidence of the recovery when compared with -60% YoY in June or -49% YoY in March. Decline in sales has also improved. It fell by 10% YoY in September whilst it declined by 18% YoY in June (Figure 1). In addition, 70% of companies recorded profits beyond market consensus, performing well against expectations overall.

The recovery is partially due to the recovery of business activities, but also the change in profit structure. Looking into September results, gross profit was down only by 10% while sales fell 10%. Normally, decline in profits against a drop in sales is disproportionately larger due to fixed costs that cannot be reduced immediately. Operating profits fell sharply by 25%, but operating margins were at 6%, doubled from 3% in the previous quarter. Margins have been recovering close to 7% YoY levels already. When looking at the sensitivity of operating income to a decline in sales (or marginal profit ratio based on actual results), it was 18% as of the end of September. The cost structure of the average Japanese company in terms of a ratio to sales is estimated to be about 25% for fixed costs, 5% for profits, and 70% for variable costs, and a standard marginal profit ratio is about 30%. Based on this, it is able to conclude that the rate of decline in profits was smaller compared with the decline in sales as of the end of September and the companies have managed to reduce costs during the period by more than we had expected.

2. Two drivers that pushed corporate change during COVID-19

While it is fair to say that these cutbacks include temporary cost reductions such as reduction in business travel and postponement of investment decisions, it is worth realizing that there were many changes in areas where the companies had not reformed though it was needed. There are two reasons why these changes were made possible: the change in the corporate dynamics which made it difficult for opponents to resist, and the environment that gives good reasons for the companies to persuade not only the company but also customers.

Shimadzu Corporation, a major measuring equipment company, has taken drastic measures, including retreat from the aircraft-related business which had been difficult to implement for a long time. While the company has been highly profitable on a company-wide basis, there was no rushing reason to retreat from the area. However, the president made a top-down decision to restructure as opposition’s voice had weakened. In the case of Kansai Paint, the president had been pushing for structural reform and digitization of operations, but progress had been limited due to internal opposition. However, taking COVID-19 situation as an opportunity, the company accelerated changes and has already delivered improved results including higher profit margins. At automobile parts companies, we are witnessing launches of overseas production facilities remotely. It was usual to send many engineering experts on site for the launch and technical education, but now it is being performed remotely by setting up proper manuals and procedures. This has led to a cost reduction and also improvement in skills of local staffs and workers.

A symbolic example of increased customer tolerance can be seen in the widespread penetration of parcel drop offs in home delivery business. In the logistics industry, which faced a serious labor shortage, the customer’s acknowledgment of drop off delivery has greatly contributed to increase drivers’ work efficiency and cost reduction. At Toppan Printing, they are reviewing "excessive quality, low-volume, high-mix production." In the printing industry, profitability was not prioritised due to excessive expectation from customers for quality at an indistinguishably high level and small lot orders utilising facilities for mass production. However, due to the readjustment of quality requirements under remote work environment and the increased demand for standard products through stay at home, order lots have increased, profitability has improved without customer complaints.

It is also a great improvement that remote sales have been accepted in the first place. At companies providing SaaS, its natural fit to the internet has led to cases where business negotiations are done remotely, contributing to an increase in sales per person. At semiconductor manufacturing equipment companies and companies like Ricoh, customers now accept special on-site operations to be conducted by local staff with Japanese experts joining online, whilst previously it was performed by Japanese experts flown in from headquarters (For example, before COVID, engineers based in Japan visit customer factories in Taiwan and China to install equipment. However, due to the pandemic, local engineers and remote workers now perform the task.) This has brought cost reduction as well as increased self-reliance of local staff.

3. Two types of changes

We have observed two types of change in the companies impacted by the two factors above. Firstly, there was cost structure reform to reduce fixed costs and bring innovations in the business process. Secondly, the companies have been able to review their business portfolio that could not have been done until now. On cost structure reform accompanied by business model innovation, there has been cutbacks in each expense item that range from personnel expenses (Dentsu reduced fixed personnel costs among employees aged 40 to 60. Those who opt for early retirement system become self-employed business owners under contract, enabling Dentsu to outsource its business), advertising expenses (Kansai Paint's profit margin in India has improved by 2 percentage points due to digitization. It has abolished paper leaflets in its retail business.), R&D costs (Denso has introduced automated tools to fix bugs in software development, has provided remote support for launching/maintenance of overseas factories, and has improved time efficiency through online meetings for customer negotiations and in- house meetings by using Zoom and Teams) to distribution costs (Hitachi Logistics provides a pay-as-you-go service for e-commerce). Technological innovations such as digitalisation and personnel measures that could not be done in normal times stand out as key drivers. The point here is that it has involved innovation of business processes and is not just a temporary or simple cost reduction exercise.

There has been a review of the business portfolio that could not have happened until now. The aforementioned review by Shimadzu Corporation and Casio Computer (which has shut down long-standing but unprofitable businesses such as projectors used in conference rooms) or JINS (which withdrew from the general store business, its foundation) are some notables. In any case, based on our interviews with the companies, COVID-19 had driven out internal oppositions and excessive micro-management by the management of companies.

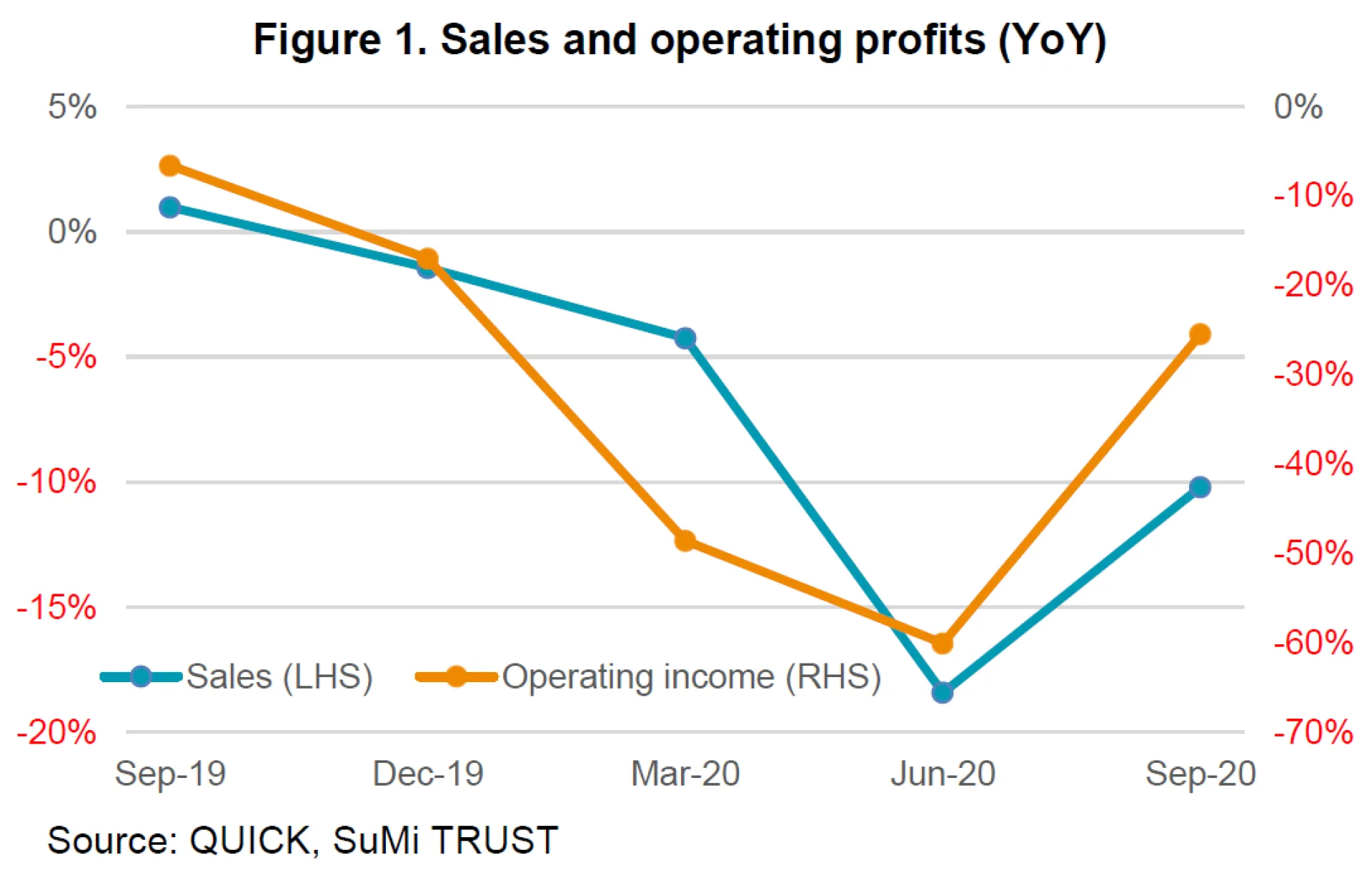

4. What companies need to do under the three forms of external pressure to change

While COVID-19 may have served as a trigger, we believe that it is a good timing for Japanese companies to change. With the introduction and gradual acceptance of the Corporate Governance Code, we are seeing a change in the composition of stable shareholders. Stewardship activities have emboldened the exercise of voting rights by institutional investors. Moreover, shareholder activism has become more prominent. In short, we are witnessing a big trend of structural change. Activists such as Murakami Fund and Steel Partners, which became hot topics in the mid-2000s, set their targets mainly on mid-sized companies. But today, activist is also focusing on large-sized companies such as Olympus and Sony. As of June 2020, about 40% of the Nikkei 225 constituent companies have been targeted by activists, and today, shareholder activism will/can exert pressure on any companies.

A private equity manager said, "It's easy to generate returns from investing in Japan. You have companies with excellent resources but poor management. Companies won’t change voluntarily, but if you exert pressure from the outside using general management tools, you can make a quick return." If the current trend of self-motivated change accelerated, we would not have to rely on external pressure and can see more cases of higher returns. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, corporate earnings and share prices depended on the sensitivity of the business structure against the pandemic. But from here on, the more critical issue is whether companies can make change happen on their own.